In the mid-16th century, Portugal stood at the center of the world’s most ambitious maritime network. From Lisbon, Portuguese ships sailed south along Africa, across the Indian Ocean, and deep into East Asia. In 1543, that vast global network unexpectedly reached Japan. What followed was one of the most remarkable first encounters in world history.

The story of Portugal’s first encounter in Japan is a reminder that Portugal’s global influence once stretched to the farthest edges of the known world and shaped culture, trade, technology, and ideas far beyond Europe. The meeting between Portugal and Japan did not last long by historical standards, but its impact continues to ripple across both sides of the globe.

Here are 15 facts that explain how Portugal first reached Japan and why it changed the trajectory of global history.

1. Portugal Reached Japan at the Height of Its Global Power.

When Portuguese sailors arrived in Japan in the 1540s, Portugal was already a global maritime power. Lisbon was a hub of international trade that linked Europe to Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and China. Portuguese navigators had mastered long-distance sea routes decades before other European nations.

Japan was not an isolated target but part of Portugal’s expanding commercial world. By the time the Portuguese reached Japanese shores, they had already established footholds in Goa, Malacca, and Macau. Japan became the easternmost point of this vast trading network, which completed a maritime arc that spanned half the planet.

2. The First Portuguese Arrival on Japanese Shores Was an Accident.

The first Portuguese to reach Japan did not arrive with a grand strategy. In 1543, a Portuguese ship was blown off course during a regional voyage and landed on the small island of Tanegashima in southern Japan.

What began as an accident quickly turned into opportunity. Local Japanese leaders were curious about the foreigners, their weapons, and their goods. The Portuguese, in turn, recognized Japan’s economic and strategic potential. This unplanned encounter marked Japan’s first direct contact with Europeans and opened the door to contact with the outside world.

3. Portugal Became Japan’s First European Gateway.

For several decades, Portugal was Japan’s primary connection to Europe. No other European nation had regular access to Japanese ports during this period. Portuguese ships carried Japanese silver, swords, and crafts outward while bringing silk, spices, firearms, and new ideas to the island country.

This exclusivity gave Portugal enormous influence over how Japan first understood Europe. Maps, clothing, religious concepts, and scientific knowledge all arrived filtered through a Portuguese lens. Japan’s initial image of the Western world was, in many ways, an image of Portugal.

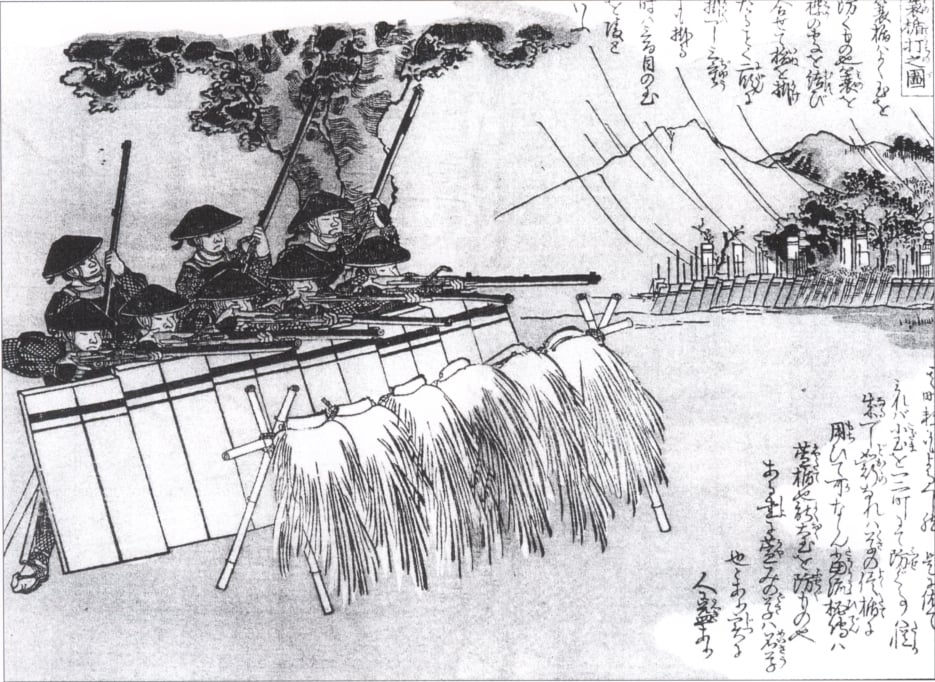

4. Portuguese Firearms Reshaped Japanese Warfare.

One of the most immediate and dramatic effects of the Portuguese landing in Japan was the introduction of firearms. The arquebus, a matchlock gun carried by the Portuguese, quickly captured the attention of the Japanese.

Japanese craftsmen rapidly learned how to reproduce and improve the weapon. Within a few decades, firearms were being manufactured domestically and deployed on a massive scale. This technological transfer played a significant role in the unification wars of the Sengoku period, which altered military tactics and power balances across Japan.

5. The Portuguese Did Not Attempt to Colonize Japan.

Unlike Portugal’s activities in parts of Africa and the Americas, the Portuguese did not ever try to colonize Japan. Their presence had commercial and religious aims rather than any territorial ambitions.

Japan was politically strong, militarily capable, and socially complex. Portuguese traders understood that success depended on cooperation with local rulers rather than conquering them. This relationship, built on negotiation and mutual benefit, distinguished Portugal’s Japanese experience from European colonial ventures elsewhere.

6. Portuguese Merchants Dominated Early European Trade With Japan.

For much of the 16th century, Portuguese merchants controlled European access to Japanese markets. Large trading ships, often departing from Macau, made annual voyages to Japan.

These voyages were highly regulated and immensely profitable. Japanese silver was especially valuable in Asian trade networks, and Portugal became a key intermediary in regional commerce. This role reinforced Portugal’s importance as a global trading nation and integrated Japan into wider economic systems.

7. The Nanban Trade Era Emerged through Portuguese Contact.

The Japanese referred to the Portuguese and other Europeans as Nanban, meaning southern barbarians, a term reflecting the direction from which they arrived. The period of interaction that followed is known as the Nanban trade era.

During this time, Japanese art, fashion, and material culture absorbed European influences. Folding screens depicted Portuguese ships and sailors. European clothing styles appeared in Japanese cities. This cultural exchange reflected the ongoing encounters between distinct civilizations.

8. Christianity Entered Japan under the Portuguese Flag.

Trade was not the only force traveling with Portuguese ships. Catholic missionaries, particularly members of the Jesuit order, arrived alongside merchants.

Portugal supported missionary activity as part of its global expansion. It viewed religion and commerce as being intrinsically intertwined. Christianity offered Japanese converts a new spiritual framework and new connections to foreign trade networks. The faith spread rapidly, especially in southern Japan, where Portuguese influence was strongest.

9. Francis Xavier Became the Face of Portuguese Missionary Work.

One of the most influential figures in early Portuguese-Japanese relations was Francis Xavier. Arriving in Japan in 1549, he was among the first Christian missionaries to preach there.

Xavier approached Japan with intellectual respect. He recognized its sophisticated culture and social order. He and other Jesuits learned Japanese, translated religious texts, and engaged local elites. Although Christianity would later face persecution, Xavier’s efforts laid the foundation for one of the fastest religious expansions in Japanese history.

10. Nagasaki Prospered Because of Portuguese Trade and Faith.

The city of Nagasaki owes much of its early growth to Portuguese activity. Initially a small fishing village, Nagasaki developed into a major port through sustained contact with Portuguese traders and missionaries.

Local leaders recognized an economic advantage in welcoming Portuguese ships and Christian institutions. Over time, Nagasaki became a cosmopolitan center where Japanese, Portuguese, Chinese, and other foreign merchants interacted. It was one of the most internationally connected cities in Japan during the 16th century.

11. Japanese Christianity Reached Tens of Thousands of Converts.

At its peak, Christianity in Japan attracted tens of thousands of followers. Some Japanese daimyo embraced the faith and experienced political and economic benefits in aligning with Portuguese traders.

Christian communities established churches, schools, and charitable institutions. For a brief period, Japan was home to one of the largest Christian populations in Asia outside European control. This rapid growth later contributed to political backlash, but it remains a striking example of early global religious exchange.

12. Portuguese Food Influenced Japanese Cuisine.

Portuguese influence extended into everyday life through food. Several Japanese culinary staples trace their origins to Portuguese cooking techniques.

Tempura is widely believed to have developed from Portuguese methods of frying battered foods. Castella cake, introduced by Portuguese traders, remains a popular dessert in Japan today. Even the Japanese word for bread, pan, comes from the Portuguese pão. These culinary legacies are among the most enduring reminders of Portugal’s presence in Japan.

13. The Portuguese Language Left Its Mark on Japanese Vocabulary.

Language was another area of cultural exchange. In addition to “pan”, several Japanese words entered the language through Portuguese contact, particularly related to trade, food, and religion.

These borrowed terms reflect practical interaction rather than abstract influence. They emerged from daily encounters between sailors, merchants, missionaries, and local communities. Linguistic traces like these offer subtle but powerful evidence of how deeply Portuguese contact penetrated Japanese society.

14. Political Suspicion Eventually Ended Portuguese Influence.

By the early 17th century, Japan’s political leadership grew increasingly wary of foreign influence. Christianity, in particular, was seen as a potential threat to social order and political authority.

As Japan moved toward national unification and stability, the Tokugawa shogunate imposed restrictions on foreign contact. Portuguese missionaries were expelled, and Portuguese ships were eventually banned. This shift marked the beginning of Japan’s long period of controlled isolation from most of the Western world.

15. Portugal Left Japan, but Its Global Impact Endured.

Although Portugal’s physical presence in Japan ended, its influence did not disappear. Firearms, food, language, and cultural memories remained embedded in Japanese society. Japan’s early understanding of Europe was shaped largely through its encounter with Portugal.

For Portugal, the Japanese chapter demonstrates its extraordinary global reach during the Age of Discovery. It shows how a relatively small Atlantic nation helped connect distant civilizations through trade, curiosity, and exchange.

Portugal’s Legacy in Japan Continues to This Day

The story of Portugal’s arrival in Japan reveals a country that once stood at the crossroads of the world and shaped global connections long before globalization became a modern concept.

Portugal’s meeting with Japan was brief but transformative. It changed how Japan fought wars, cooked food, practiced religion, and understood the wider world. It also confirmed Portugal’s place as one of history’s great connectors of cultures, ideas, and people.

That legacy remains part of Portugal’s identity, written in history books, kitchens, languages, and shared global memories.