Christmas occupies a unique place in Portuguese literature. The season is not treated as pure celebration. It is often reflective, sometimes melancholic, and filled with questions of belonging, faith, family, and memory. Some poets write about the Nativity through a rural lens while others through the doubt or distance of modern life. These poems have become part of Portuguese seasonal culture and appear frequently in December magazines, school materials, and public readings.

Below are four Christmas poems and one short story from Portugal including their English translations. We hope you enjoy them!

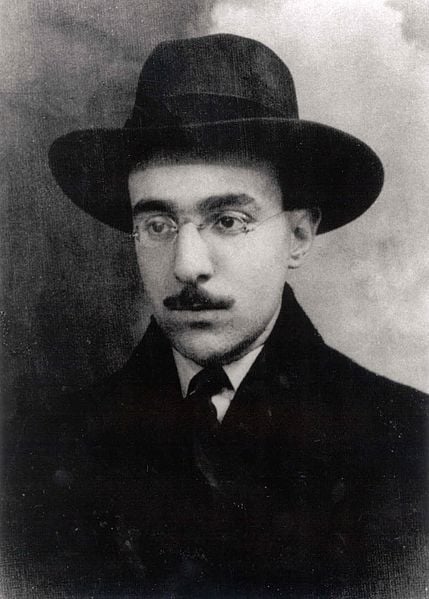

1. “Chove. É Dia de Natal” by Fernando Pessoa

This is one of the best known Portuguese Christmas poems from Portugal’s most famous poet. It surprises readers with its refusal to sentimentalize the holiday. Pessoa presents a Christmas where the weather, the cold, and the narrator’s own detachment set the emotional tone.

Chove. É dia de Natal.

Lá para o Norte é melhor:

Há a neve que faz mal.

E o frio que ainda é pior.

E toda a gente é contente

Porque é dia de o ficar.

Chove no Natal presente.

Antes isso que nevar.

Pois apesar de ser esse

O Natal da convenção,

Quando o corpo me arrefece

Tenho o frio e Natal não.

Deixo sentir a quem quadra

E o Natal a quem o fez,

Pois se escrevo ainda outra quadra

Fico gelado dos pés.

It’s raining. It’s Christmas Day.

It’s raining. It’s Christmas Day.

Up north it’s better:

There’s snow, which is bad,

And cold, which is even worse.

And everyone is happy

Because it’s a day to be happy.

It’s raining on Christmas Day.

Better that than snow.

Because even though it’s

The conventional Christmas,

When my body gets cold,

I feel the cold, but not Christmas.

I’ll leave it to those who feel it

And to those who made Christmas,

Because if I write another verse,

My feet will freeze.

Pessoa’s Christmas is a psychological landscape. It is shaped not by religion or family joy, but by rain and emotional distance. The poem is famous because it acknowledges a truth many recognize during the holidays. Christmas does not automatically create the feelings people expect. The poem reminds us that the season can highlight whatever mood we already carry inside.

2. “Natal na Província” by Fernando Pessoa

Another well known Christmas poem by Pessoa appeared in the 1920s and has been widely anthologized. It shows a nostalgic vision of the provinces contrasted with the narrator’s sense of separation.

Natal… Na província neva.

Nos lares aconchegados,

Um sentimento conserva

Os sentimentos passados.

Coração oposto ao mundo,

Como a família é verdade!

Meu pensamento é profundo,

Estou só e sonho saudade.

E como é branca de graça

A paisagem que não sei,

Vista de trás da vidraça

Do lar que nunca terei!

Christmas… It snows in the province.

In cozy homes,

A feeling preserves

Past emotions.

Heart opposed to the world,

How true family is!

My thoughts are deep,

I am alone and dream of longing.

And how white with grace

Is the landscape I don’t know,

Seen from behind the windowpane

Of the home I will never have!

This poem is notable for moving between warmth and sorrow. While snow, hearths, and family rituals suggest coziness, Pessoa places himself outside the circle. Pessoa’s feelings of loneliness creates a tension between idealized Christmas scenes and the emotional truths that can lie beneath them.

3. “Natal” by Miguel Torga

Miguel Torga created some of the most cherished Christmas imagery in Portuguese poetry. His work often draws on rural life, hardship, and the dignity of the common people.

Foi tudo tão pontual

Que fiquei maravilhado.

Caiu neve no telhado

E juntou-se o mesmo gado

No curral.

Nem as palhas da pobreza

Faltaram na manjedoira!

Palhas babadas da toira

Que ruminava a grandeza

Do milagre pressentido.

Os bichos e a natureza

No palco já conhecido.

Mas, afinal, o cenário

Não bastou.

Fiado no calendário,

O homem nem perguntou

Se Deus era necessário…

E Deus não representou.

Everything was so punctual

That I was amazed.

Snow fell on the roof

And the same cattle gathered

In the corral.

Not even the straws of poverty

Were missing from the manger!

Straws drooled by the cow

That ruminated on the greatness

Of the miracle she sensed.

The animals and nature

On the familiar stage.

But, in the end, the setting

Was not enough.

Trusting in the calendar,

Man did not even ask

If God was necessary…

And God did not appear

Torga’s Christmas contrasts the severity of winter with a sudden burst of radiance. The Nativity is a humanizing force, an eruption of warmth in a harsh world. His vision has resonated across rural Portugal, where winter was historically difficult and where the birth of Christ symbolized hope rooted in earthly experience.

4. “A Noite de Natal” by Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen

You might notice from our excerpt below that A Noite de Natal is a short story and not a poem, but Sophia de Mello Breyner’s beautiful and timeless book, published in 1959, is a timeless classic in Portugal. We have included an excerpt below for your reading pleasure.

— Boa noite — disse ela. — O meu nome é Joana. E vamos com a estrela.

— Também eu — disse o rei — caminho com a estrela e o meu nome é Baltasar.

E juntos seguiram os quatro através da noite.

No chão, os galhos secos estalavam sob os passos, a brisa murmurava entre as árvores e os grandes mantos bordados dos três reis do Oriente brilhavam entre as sombras verdes, roxas e azuis.

Já quase no fundo dos pinhais viram ao longe uma claridade. E sobre essa claridade a estrela parou.

E continuaram a caminhar.

Até que chegaram ao lugar onde a estrela tinha parado e Joana viu um casebre sem porta. Mas não viu escuridão, nem sombra, nem tristeza. Pois o casebre estava cheio de claridade, porque o brilho dos anjos o iluminava.

E Joana viu o seu amigo Manuel. Estava deitado nas palhas entre a vaca e o burro e dormia sorrindo.

Em sua roda, ajoelhados no ar, estavam os anjos. O seu corpo não tinha nenhum peso e era feito de luz sem nenhuma sombra.

E com as mãos postas os anjos rezavam ajoelhados no ar.

Era assim, à luz dos anjos, o Natal de Manuel.

— Ah — disse Joana — aqui é como no presépio!

— Sim — disse o rei Baltasar — aqui é como no presépio.

“Good evening,” she said. “My name is Joan. And we’re going with the star.

“Me too,” said the king, “way with the star and my name is Balthasar.

And together they followed the four through the night.

On the ground, the dry branches slapped under the footsteps, the breeze murmured among the trees and the large embroidered cloaks of the three kings of the East shone among the green, purple and blue shadows.

Almost at the bottom of the pine forests saw in the distance a clarity. And about that clarity the star stopped.

And they continued to walk.

Until they got to the place where the star had stopped and Joan saw a doorless hut. But he saw no darkness, no shadow, no sadness. For the hut was full of clarity, for the brightness of the angels illuminated it.

And Joan saw her friend Manuel. He was lying in the straws between the cow and the donkey and sleeping smiling.

On his wheel, kneeling in the air, were the angels. His body had no weight and was made of light without any shadow.

And with their hands placed the angels prayed kneeling in the air.

Thus, in the light of the angels, Manuel’s Christmas.

“Ah,” said Joan, “here is how in the nativity scene!

“Yes,” said King Balthasar, “here is as in the nativity scene.

A Noite de Natal by Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen is widely regarded as a classic of Portuguese Christmas literature, recognized both for the author’s stature and for the story’s deep cultural presence. First published in 1959 in Histórias da Terra e do Mar, it has long been included in school curricula, frequently appearing in Portuguese language lessons during the holiday season. Many families keep Sophia’s children’s books at home, and this tale is often read aloud at Christmas, becoming part of household tradition. Over the decades it has also been adapted for theater, radio, and school plays, reinforcing its visibility and emotional resonance. Although not every home revisits it each year, the story remains a cherished and enduring fixture of Portugal’s Christmas canon.

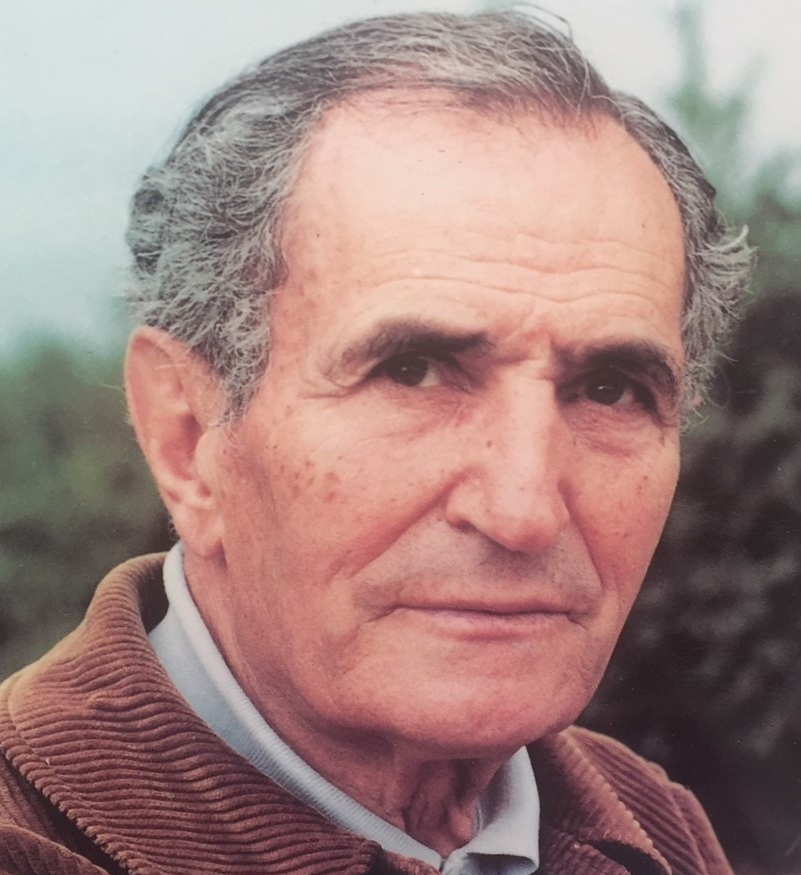

5. “Tangerinas de Natal” by João Luís Barreto Guimarães

Born in Porto in 1967, João Luís Barreto Guimarães earned his medical degree from the University of Porto and went on to build a dual career as both a surgeon and a celebrated poet. He debuted in literature with Há Violinos na Tribo in 1989, and his poetry has been published widely across Europe and the Americas. In addition to being a poet, he is a plastic, reconstructive, and aesthetic surgeon at the Hospital Center of Vila Nova de Gaia. Over the years, he has received numerous awards, including the United Nations Creativity Award, the National Prize for Poetry, Bertrand’s Book of the Year, and the prestigious Pessoa Prize in 2022.

«Será que eles ainda fazem?» É

domingo

para segunda. Resolves

a teu favor a

última tangerina e devolves a pergunta:

«Os meus ou

os teus?» E eu sorrio. Há quem os

queira exprovados quase

que imaculados

mesmo sabendo-nos prova de

que tiveram de fazer para

agora aqui estarmos

negociando imperfeições.

«Deixei-te ficar na dúvida.»

«Lembras-te de cada coisa . . . »

Atalhas-me com o

gomo perfeito mas

eu quero mais de ti

«Estás a ficar com sono.»

«Continua.»

“Do they really still do it?” It’s

Sunday

going on Monday. You take it

upon yourself to have the

last tangerine and return the question:

“Mine or

yours?” And I smile. There are those

who want them pristine almost

immaculate

even knowing ourselves to be proof

of them having done it for

us to be here now

debating imperfections.

“I left you wondering”

“The things you think about . . .”

You cut me short with the

perfect wedge but

I want more from you

“You are getting tired.”

“Keep going.”

Tangerines are a familiar part of Christmas in Portugal because they are in peak season during December and have long been included in traditional holiday Portuguese foods. Before imported sweets were common, many families relied on seasonal fruit for festive treats, so citrus became a staple alongside nuts, figs, and homemade pastries. Their bright color and fresh scent also symbolize warmth and abundance during winter, and they frequently appear in Christmas gift baskets and family tables. While the answer to Barreto Guimarães’s opening question “Do they really still do it?” is unclear to a first-time reader, it can be ascertained that the author might be referring to the tradition of giving tangerines during the Christmas holidays in Portugal. Maybe so. Maybe not, but the imagery and connection between the two people at the table is beautiful and memorable, a shared moment that the author wants more of.

Christmas Poetry in Portugal

Portuguese writers treat Christmas as a study in contrasts. Joy and sorrow, warmth and cold, faith and doubt, memory and longing all come together in December year after year. These poems are famous because they reflect real experiences. Like in so many countries, in Portugal, Christmas is a time when people look back on the year, think about loss, and hope for renewal.