Portuguese may look familiar to English speakers on the surface, but it hides a few sneaky surprises. False friends, which are those innocent-looking terms that look like English words but mean something totally different, can catch even long-time learners off guard. Even when you’re trying to impress a local, order lunch, or just get through a door, these words can betray you in a split second.

This guide focuses on false friends specifically in European Portuguese. We want to help you avoid common traps and learn the correct vocabulary. With each of these 15 sets of false friends, we explain the confusion, show you what the word really means, and give you two real-world examples to help you sound more fluent and natural in your conversations. Are you ready? Let’s go!

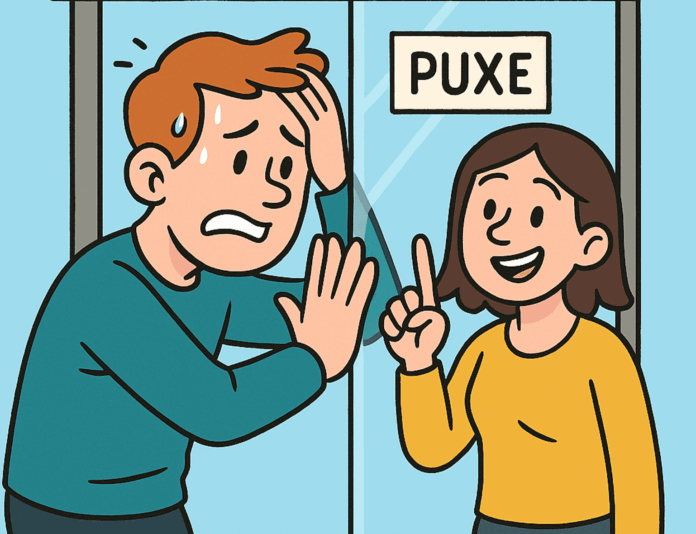

1. Puxe ≠ Push

At first glance, this one looks like it’s inviting you to push the door, and you will see this on countless doors across Portugal. But – beware! – in European Portuguese, “puxe” actually means pull and comes from the verb puxar. It’s probably the most classic divider between English speakers who understand Portuguese and those who don’t that you can actually watch in real time. Just approach every door with caution in Portugal until you get this right!

The correct word for push is empurre (from empurrar).

Examples

– Tentei empurrar a porta, mas depois reparei que dizia “Puxe”.

(I tried to push the door, but then I noticed it said “Puxe.”)

– Empurre com força. A porta está um pouco presa.

(Push firmly. The door is a bit stuck.)

2. Constipação ≠ Constipation

No, Portuguese people aren’t constantly talking about digestion. In Portugal, having a constipação means you’ve caught a cold, not that you’re, well, backed up. If you do need to talk about actual constipation, use prisão de ventre or obstipação.

Examples

– Estou com uma constipação horrível — só me apetece ficar na cama.

(I’ve got a horrible cold — I just feel like staying in bed.)

– A mudança na alimentação causou-lhe prisão de ventre.

(The change in diet caused her constipation.)

3. Êxito ≠ Exit

Although this word resembles “exit,” êxito means success in Portuguese. You’ll see it in newspaper headlines and book reviews, not on fire doors. The word for exit is saída, which you will see everywhere!

Examples

– O cantor teve muito êxito no Festival da Canção.

(The singer had great success at the Song Festival.)

– A saída de emergência está claramente assinalada.

(The emergency exit is clearly marked.)

4. Notícia ≠ Notice

It might sound like a friendly reminder or a memo, but notícia means news, something you read in the paper or hear on the radio. For a notice, such as a posted sign or a warning, use aviso. You will see this word frequently.

Examples

– Acabei de ver uma notícia impressionante sobre o sismo.

(I just saw an impressive news story about the earthquake.)

– Houve um aviso de tempestade emitido pela Proteção Civil.

(There was a storm warning issued by Civil Protection.)

5. Enrolar ≠ Enroll

This one trips people up in writing and speech. Enrolar means to roll up, physically or metaphorically (like stalling). If you want to say enroll in a course or program, use inscrever-se.

Examples

– Enrolaste bem o cabo ou ainda está solto?

(Did you roll the cable properly or is it still loose?)

– Já me inscrevi no curso de fotografia.

(I’ve already enrolled in the photography course.)

6. Livraria ≠ Library

Don’t go into a livraria expecting to borrow books. You’ll be expected to buy them! Livraria means bookstore. A library is called a biblioteca in Portuguese. Because the Portuguese love their books, you’re going to see these two words everywhere!

Examples

– A nova livraria tem uma secção fantástica de autores portugueses.

(The new bookstore has a fantastic section of Portuguese authors.)

– Costumo estudar na biblioteca da universidade.

(I usually study at the university library.)

7. Taxa ≠ Tax

Although the spelling is similar, taxa usually refers to a rate or fee, like interest rates or service charges. If you’re talking about a government tax, use imposto.

Examples

– A taxa de natalidade tem vindo a diminuir.

(The birth rate has been decreasing.)

– Os impostos sobre combustíveis vão aumentar novamente.

(The taxes on fuel are going to increase again.)

8. Ofício ≠ Office

Ofício means a profession, craft, or even a formal written notice, depending on the context. It’s not where you go to work. The word for office is escritório.

Examples

– O seu ofício era o de ferreiro, tal como o pai.

(His profession was that of a blacksmith, just like his father.)

– Cheguei atrasado ao escritório por causa do trânsito.

(I was late to the office because of traffic.)

9. Costume ≠ Costume

This is a subtle but important one. Costume refers to a habit, tradition, or custom.

If you’re talking about clothing (like a superhero costume or a swimsuit), the word is fato.

Examples

– É costume beber um copo de vinho com o jantar em Portugal.

(It’s customary to drink a glass of wine with dinner in Portugal.)

– Ela trouxe o fato de banho mas esqueceu-se da toalha.

(She brought her swimsuit but forgot the towel.)

10. Assistir ≠ Assist

This can be especially confusing in conversation. Assistir means to watch or attend, not to help. To assist someone, you need ajudar.

Examples

– Vamos assistir à apresentação do novo livro.

(We’re going to attend the presentation of the new book.)

– Ele ajudou-me a montar o móvel da IKEA.

(He helped me assemble the IKEA furniture.)

11. Atualmente ≠ Actually

Despite looking just like “actually,” atualmente means currently or nowadays. To express “actually” in the sense of clarifying or correcting, use na verdade.

Examples

– Atualmente vivo em Setúbal, mas nasci em Braga.

(Currently I live in Setúbal, but I was born in Braga.)

– Na verdade, nunca fui a Paris, só a Lyon.

(Actually, I’ve never been to Paris, only to Lyon.)

12. Colégio ≠ College

A colégio in Portugal is typically a private primary or secondary school. The correct word for a university-level college is faculdade.

Examples

– O colégio onde andei era só para meninas.

(The school I attended was for girls only.)

– Entrei na Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

(I was accepted into the Faculty of Arts at the University of Porto.)

13. Data ≠ Data (as in information)

Here’s a sneaky one: data in Portuguese means calendar date.

For the data you input into a form or analyze in a spreadsheet, use dados.

Examples

– A data do evento foi alterada para setembro.

(The date of the event was moved to September.)

– Introduz os teus dados pessoais neste formulário.

(Enter your personal data into this form.)

14. Novela ≠ Novel

Novela in Portugal is a soap opera, usually a dramatic TV series watched after dinner.

If you’re talking about a novel, use romance.

Examples

– A novela da noite tem sido muito comentada nas redes sociais.

(The evening soap opera has been widely discussed on social media.)

– Gosto de ler romances históricos nas férias.

(I enjoy reading historical novels during holidays.)

15. Lanche ≠ Lunch

Lanche refers to a snack, typically eaten in the afternoon around 5:00 PM.

The Portuguese word for lunch is almoço.

Examples

– Comi um lanche leve antes do treino: uma maçã e um iogurte.

(I had a light snack before training: an apple and a yogurt.)

– O almoço de hoje foi arroz de polvo – uma delícia!

(Today’s lunch was octopus rice – delicious!)

How to Stay One Step Ahead of False Friends

False friends are just waiting to trip you up on your Portuguese learning journey. They look trustworthy, they sound familiar, and then -bam! -they make you say something completely unintended. The good news is that once you know them, they’re easy to remember.

A few tips to help you avoid these mistakes:

- Read Portuguese in context. Read books, news articles, and signs to see how words are actually used.

- Practice with locals. If you say constipado and someone gives you a strange look, just laugh it off and learn from it.

- Double-check in a dictionary. Not all words that look familiar mean what you think they do.

Finally, remember – even native speakers from different Portuguese-speaking countries sometimes misunderstand each other. So don’t be too hard on yourself. Mistakes are part of the fun, and they make great stories later on!