In the mid-16th century, Portugal commanded one of the world’s most extensive maritime networks. Portuguese ships connected Europe to Africa, India, and beyond and reached ever deeper into Asia. In 1557, this vast trading empire found a permanent foothold in a small peninsula on China’s southern coast. What followed was a unique chapter in global history that would last over 400 years.

The story of how Portugal ended up in Macau reveals a relationship unlike any other European presence in Asia. Macau became the bridge between East and West, transformed global trade and cultural exchange, and was built on negotiation rather than conquest. Though Portugal’s time there officially ended in 1999, the legacy of this remarkable encounter continues to shape both nations.

Here are 12 astounding facts that explain how Portugal reached Macau and why it mattered to on a global scale.

1. Portugal reached China after decades of failed attempts.

When Portuguese traders first arrived in Chinese waters in the early 16th century, they faced immediate hostility. Portugal’s conquest of Malacca in 1511 had angered the Sultan, who promptly sent warnings to the Chinese about these aggressive foreigners.

Early Portuguese attempts to establish trading posts ended in disaster. In 1517, a diplomatic mission led by Tomé Pires reached China, but Portuguese misbehavior elsewhere on the coast doomed the effort. Pires was imprisoned and died in Canton. In 1521 and 1522, Portuguese ships attempting to trade near Canton were driven away by Ming authorities. The path to establishing a permanent presence in China would require patience, cooperation, and a change in tactics.

2. Pirates became Portugal’s unexpected allies.

The turning point came when Portuguese traders helped Chinese authorities solve a serious problem: coastal piracy. In the 1540s and early 1550s, pirates plagued the southern Chinese coast, disrupted trade, and threatened local communities.

Portuguese ships, armed with superior naval firepower, assisted Chinese officials in eliminating these pirates. This cooperation rebuilt trust between the Portuguese and Chinese authorities. By demonstrating their value as military allies rather than threats, the Portuguese opened the door to negotiation. What had seemed impossible just decades earlier suddenly became achievable.

3. Macau was rented by the Portuguese instead of being conquered.

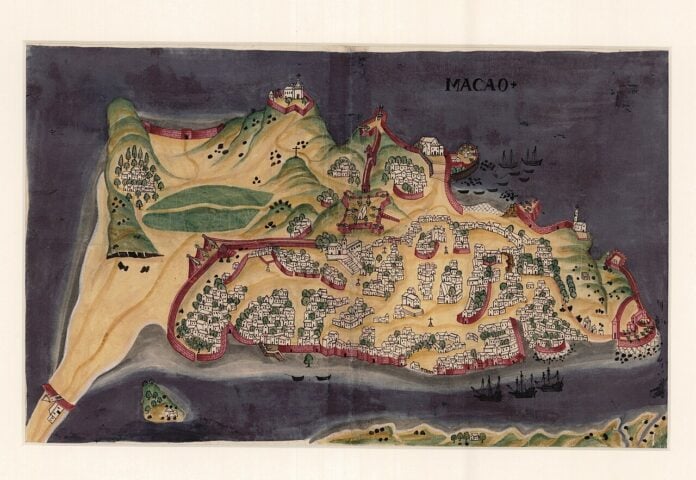

In 1557, the Ming Dynasty granted Portugal permission to establish a permanent trading settlement in Macau. Portugal paid an annual ground rent of 500 taels of silver to Chinese authorities.

This arrangement was unique in Portugal’s global empire. Unlike territories in Africa, India, or the Americas, Macau remained under Chinese sovereignty. The Portuguese administered the settlement but had no territorial claims. This relationship of mutual benefit, built on trade rather than domination, allowed Macau to prosper for centuries. China maintained ultimate authority while benefiting from Portuguese commercial connections.

4. The name “Macau” came from a temple.

When Portuguese traders first landed on the peninsula, they asked local residents what the place was called. The locals, believing the foreigners were asking about the nearby A-Ma Temple, dedicated to the goddess of seafarers, replied “Ma-ge,” meaning Temple of Ma.

The Portuguese heard this as the name of the entire territory. Over time, “Ma-ge” evolved into “Macau” in Portuguese pronunciation. This misunderstanding created a name that would become known worldwide. The temple that gave Macau its name still exists today, a reminder of the settlement’s origins.

5. Macau became the hub of a triangular trade route.

From 1557 until 1639, Macau thrived as the center of the China-Macau-Japan triangular trade. This was one of the most profitable commercial routes in history. The Portuguese bought silk and gold in China, transported it to Japan, and exchanged it for Japanese silver.

The profits were extraordinary. Chinese silk was in high demand in Japan, where it sold for prices far above its cost in China. Japanese silver, meanwhile, was cheaper in Japan than in China. Portuguese traders exploited these price differences as they bought low in one market and sold high in another. This triangular trade made Macau incredibly wealthy and cemented Portugal’s role as a global trading intermediary.

6. Massive cargo ships called carracks sailed from Macau to Japan every year.

Annual trading voyages between Macau and Japan were conducted by massive cargo ships called carracks. The Japanese called these vessels kurofune, or “black ships,” because of their dark, treated hulls designed to resist marine parasites.

These ships could carry between 300 and 1,600 tons of cargo and hundreds of people. Departing from Macau, they would sail to Nagasaki loaded with Chinese silk, porcelain, gold, and goods from across the Portuguese trading network. They returned with Japanese silver, copper, lacquerware, and other valuable products. The voyage monopoly was so profitable that the right to command it was awarded annually by Portuguese authorities as a reward for service.

7. Portuguese missionaries made Macau a gateway to Asia.

Macau became the headquarters for Catholic missionary work throughout Asia. Jesuit missionaries used Macau as a base to launch religious expeditions into China, Japan, and beyond.

Pope Gregory XIII recognized Macau’s religious importance by creating the Diocese of Macau in 1576. This made the small settlement one of the most significant centers of Catholicism in Asia. Missionary institutions like the Colégio de São Paulo trained priests and missionaries who would spread Christianity across the region. The Jesuits, in particular, gained influence at the imperial court in Beijing. They used their position to protect Macau from excessive Chinese demands.

8. Macau survived a major Dutch invasion.

In 1622, the Dutch East India Company attempted to capture Macau. A force of 800 Dutch soldiers landed at Cacilhas, on the eastern edge of the peninsula, intending to seize the prosperous trading port.

The defenders numbered only about 150 Portuguese and Macanese along with African slaves. Despite being heavily outnumbered, they successfully repelled the invasion. Portuguese cannons and defensive positions, combined with determined resistance, inflicted heavy casualties on the Dutch attackers. The Dutch commander was wounded and evacuated. This victory secured Macau’s independence and led to the construction of stronger fortifications including the Guia Fortress.

9. Macau’s Golden Age ended when Japan closed its doors.

Macau reached its peak prosperity between 1595 and 1602, a period historians call its “Golden Age.” The settlement was one of the busiest commercial cities in East Asia and served as an entrepôt for Portuguese and Spanish trade routes.

This golden age ended abruptly in 1639 when Japan expelled all Portuguese traders and banned foreign ships. The Tokugawa Shogunate, suspicious of Christianity and foreign influence, sealed Japan off from the outside world. The loss of the Japan trade route was catastrophic for Macau. The triangular trade that had made the settlement wealthy vanished overnight. Macau’s economy went into severe decline and forced merchants to seek new trading partners and routes.

10. Macau found new life trading with Southeast Asia.

After losing access to Japan, Macau redirected its commercial energy toward Southeast Asia. Portuguese traders developed new routes to Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Trade with Manila became particularly important.

The Portuguese reached an agreement with Spanish authorities in Manila and became the primary suppliers of Chinese goods to the Philippines. Ships sailed from Macau to Manila carrying silk, porcelain, furniture, and other Chinese products. They returned with silver from Latin American mines, which was then used to purchase more goods in China. Though never as profitable as the Japan trade, these Southeast Asian routes kept Macau economically viable.

11. Other European powers challenged Portugal’s monopoly.

In 1685, the Chinese Emperor authorized trade with all foreign countries, which effectively ended Portugal’s privileged position as the exclusive intermediary between China and Europe. British, Dutch, French, Danish, Swedish, American, and Russian traders all established offices in Canton and Macau.

This competition diminished Macau’s special status. No longer the only European gateway to China, Macau had to adapt to a more crowded commercial landscape. In 1757, Chinese authorities further restricted foreign traders and allowed them to reside in only one place in Chinese territory: Macau. This gave the settlement renewed importance as the sole European residence permitted in China, even as its trading monopoly disappeared.

12. Macau became an official Portuguese colony only in 1887.

For over three centuries, Macau existed in a unique legal gray area. Portugal administered the settlement and paid rent to China, but sovereignty remained ambiguous. The Portuguese considered it a colony, while China maintained it was Chinese territory under Portuguese administration.

This ambiguity ended in 1887 when China and Portugal signed the Sino-Portuguese Treaty of Peking. China formally recognized Portuguese sovereignty over Macau. This treaty transformed Macau from a rented trading post into an official colony of the Portuguese Empire. The settlement remained Portuguese territory for another 112 years, until the handover to China in 1999, which made it the last European colony in Asia.

Portugal’s Legacy in Macau Endures

The story of how Portugal ended up in Macau demonstrates how diplomacy and trade could create lasting connections across cultures. Unlike colonial ventures built on conquest, Macau emerged from negotiation, mutual benefit, and centuries of careful relationship-building.

Macau’s unique blend of Portuguese and Chinese architecture, cuisine, and culture reflects this extraordinary history. The settlement that began as a solution to piracy became a bridge between civilizations. It facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and people across vast distances. Portugal’s presence in Macau lasted 442 years, much longer than most empires endure.

That legacy lives on in Macau’s UNESCO World Heritage sites, its Portuguese-influenced Cantonese cuisine, its bilingual street signs, and its role as a special administrative region of China. You can even visit the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre Museum in Lisbon to see artifacts and memorabilia from Macau and Portugal’s incredible history.

The story of Portugal and Macau is a reminder that global connections were being forged long before our modern era, and that those connections were built through power but also patience, adaptation, and respect.